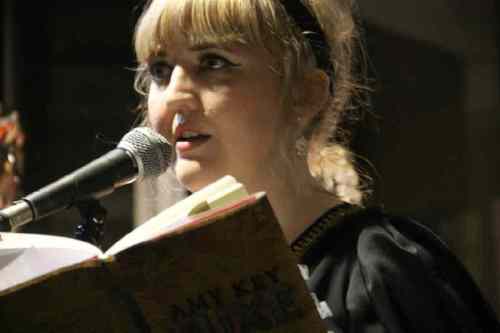

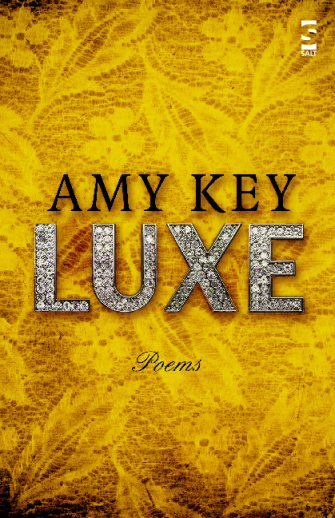

Amy Key was born in Dover and grew up in Kent and the North East. She now lives and works in London. She co-edits the online journal Poems in Which. Her pamphlet Instead of Stars was published by Tall Lighthouse in 2009, and her first collection, Luxe, was recently published by Salt. Amy is currently editing a new anthology of poems on female friendship Best Friends Forever, due from the Emma Press in November.

“Luxe (Salt Publishing, 2013) is a magnificent spree in a bric-a-brac shop. A haul of pre-loved and glittering objets – pralines in a crystal bowl, a handful of tame ladybirds, a portrait in vinyl and cola-cubes – are artfully displayed on the poems’ shelves to represent the conflicts and connections of a fabulous circle of friends and lovers, those real, remembered and imagined.”

*

“”Layer your pulse/ onto my pulse,” she writes in ‘Brand New Lover’. “Dress me.” Only the reader knows if this is an order, an instruction or the sweetest sort of invitation. Read a copy of Luxe, keep it next to your fainting couch.”

– Julia Bird

“This delicious selection is a chocolate-box assortment of the work of one of my favourite poets writing today. Her delicate, dextrous writing belies the raw truths she tells. There are many centres to her confections that only reveal themselves when you take a bite. In her words “Poem with peep toes … Poem to conceal some feelings in … Poem to avalanche in your heart”. I love Amy Key.”

– Lauren Laverne

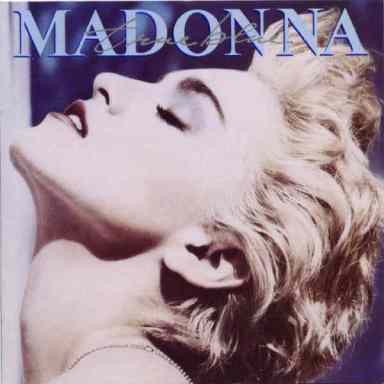

“If we are living in the material world, I want Amy Key to be my material girl. She makes her pleats and flounces move; she crowds the surface with colour and texture right where it needs to be to draw the reader in like a bee to the velvet bell of the foxglove; or like the silverscreen beauty who eats bonbons from a satin box, she wills our gaze to take it all in and to crave more. These poems are worn on the body, and like all great ensembles, they show just enough; they are hot and memorable.”

– D.A. Powell

You Ought To Be In Pictures

In my depression the energy goes everywhere. It’s diffused. And where it’s intense it’s in very short bursts. Enough to scrub the bathroom or change the sheets. Enough to write a poem. My book is as though I pressed play and record each time I had a burst.

Last night I posted lines from my iPhone notes disguised as Twitter and Facebook status updates to see if any of them stuck.

I read someone else’s poetry for the first time and worry that my book will be perceived as being derivative of their book.

Someone asks “What is your poetry about?” I am embarrassed and say “me” but I mean “being a woman”, I think. But then I really mean “my experience of being a woman”. Later I wonder if what I really mean is “what I want my experience of being a woman to be, distress included”. I’d asked the poet Kate Kilalea to read my book and respond to it. She said:

“Aside from all their purely poetic elements, what strikes me most about Amy’s poems is the kind of idea of woman-ness which they work with. It feels like what is happening is a kind of valorisation – as oppose to eroticisation – of feminine vulnerability, which is different from what I’ve seen before.”

This was an important moment for me. An embracing of the woman-ness. After all I had the comment “I can see why girls like your poems” ringing in my ears.

My poetry is endless recalibration of experience.

My poetry is a way of mind-mapping my insecurities.

It’s all mood board.

I’m struck by what Steve Roggenbuck says in his essay ‘toward a more flowing culture’:

“i want to be your poet … i want to inspire you and talk to you. in many cases, I really want to be your friend.”

This idea of friendship compels me.

In my poems am I trying to communicate more effectively with people in my life or who might be in it. To say “Look! I know I come across ‘this’ way, but here is something else I want to share”. This being able to talk without my physical persona intruding is something I need. There are so many ways into the truth of a person.

In the documentary Grey Gardens there is a scene where Little Edie performs to camera. She sings and dances to ‘You Ought To Be In Pictures’. I find this scene very touching. Little Edie is a star, but she’s no longer the ingénue, about to be discovered. In singing it she’s saying to the crew “Look at me. I could have been someone” but also “Tell me I still could be someone”. It’s the “Tell me I could still be someone” that affects me. In my poem ‘On Typing Paper Stolen From Her Employers She Proceeds To Evolve A Campaign’ I get at this idea:

Hopes should recede with age but this isn’t

a right seeming present!

[…]

My imagined future is a collapsed soufflé.

Never far away from dancing to ‘True Blue’ in the kitchen a grown-up’s face on. Never far from singing into the cassette. Singing into the dark. Hopeful someone will say what a nice voice you have. Never far away from maybe making it.

Just as Alabama, the main character in Zelda Fitzgerald’s Save Me The Waltz, in her hopeless pursuit of ‘making it’ as a ballet dancer feels that:

“[in] reaching her goal…in proving herself, she would achieve that peace which she imagined went only in surety of one’s self – that she would be able, through the medium of the dance, to command her emotions, to summon love or pity or happiness at will, having provided a channel through which they might flow”

I am my own delusional heroine. But I have to hope.

I am also forcing people to look at me. In my poem ‘Emotional State Seen Through A Pale-Haired Fringe’ I am, chronologically speaking, at the beginning of a deep depression. Unable to speak about it to anyone, just quietly falling apart, I write the poem where even:

[…] the at-boil kettle maddens the bully

of your memory, and no one there to see it blow.

Is it that I’m terrified of no one seeing me live? Is that the role poetry is playing?

I’ve often wondered if I write poetry because I’m scared of dying. I fear I’ve been negligent of my own fortune.

Inside I fritter soft as cinders.

One of the recurring images in my poetry is of the lost child. The much loved children’s book Where The Wild Things Are was made into a film a few years ago and I became obsessed with it. And heartbroken by it, by the isolation of the boy and his imagination. I began to write a series of poems, inspired by the film and by the soundtrack to the film, written and performed by Karen O from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. The poems turned out as childhood memoir and in implicating my siblings I found I couldn’t finish them. One has made the book – Igloo – and in it I try to express the self-imposed, necessary isolation of the child:

[…] Instead of talk,

we will have stronger thoughts.

This is both a resistance to talking – there are some things I cannot speak to the adults about but it is also a power I can have. The idea of having secrets that I can snap into being, like activating a glow stick appeals to me. The secret as super power and malevolent force.

I should really talk about love.

When I was in John Stammers’ group he asked me ‘what I wanted to be’. I told him I wanted to be ‘a great love poet’.

What I really meant was ‘I want to be loved’.

This was some years ago now. Truth is my experiences in and out of love haven’t been at all happy, but it seems to be all I can write about. Perhaps that’s the recalibration I mentioned earlier. A need to ‘right’ my love experience in poetry. In my poem ‘Your Year in Review’ I address myself:

[…] Your heart went rouge. Desire

kept in a gold compact, fell loose of its casing. Powder

went everywhere.

The sense that I make a mess of stuff can’t be escaped. But I lavish my attention on love less experienced, more felt. In absence of the grand, all-consuming Love Affair (in the presence of the paltry, ill-conceived ones) I act them out in poems. My nights pour into the absence of my One True Love. But I know:

Even this crochet blanket won’t

address the lack of requited laundry.

Really my ‘it would be better to be hurt than not have any love at all’ from my teenage diary is simply reworn as:

[…] rather a cupboard of cut-off ponytails than this! I want a life

that warrants excessive exclamation!

I suspect all the poems are just an attempt to neutralise my self-image.

Brand New Lover

I’ve abandoned vanity, since I became a body

of pixels, never quite set, since you rippled

the apparent skin of me.

I’m all texture. Silk rosette, billowing coral,

tentative as a just baked cake. Sensations

slide over my knitted blood.

My mouth is a glass paperweight

to keep our tastes in, like maraschino

cherries and water from a zinc cup.

This is not about a future

with a decorative child. Layer your pulse

onto my pulse. Dress me.

*

To A Clothes Rail

Dress folded as an envelope and posted to me

Hand-me-down dress taken up, then taken down again

The one worn once, to a party

Age-appropriate dress

Dress the colour of your skin long underwater

Margot dress, Marianne dress, Marie-Antionette dress

Paper dress, never worn, purely decorative

Dress employed as stand-in

Silk dress with scenes from Labyrinth

Pattern for a dress, unmade

Dress embroidered with every song I’ve ever loved

Pinafore that comes with caveats

Two sizes too small dress, bought for its primrose

One last seen doing the hula down the precinct

Shift once worn in a dream

Dress as though assembled from vegetable peelings

Woodland dress in the style of a fawn

Poppy-print shirtwaist, won in a tombola

Dress for slow-dancing to ‘Anyone Who Knows What Love Is (Will Understand)’

Fancy dress in want of a petticoat

Cocktail-drinking dress, un-sittable-down in

Dress best worn with brutalist pendant

Smock to bring to mind a meadow

Old-fashioned dress in crepe with self-covered belt

Little black dresses (numerous)

Acid light projections dress for crazing the eyes

Formal wear gown for selling on eBay

Dress bought for funeral, frequently worn to detach from death

Dress last worn when someone cried for you

Fretful dress, to be cut up for rags

Palladium dress for looking into mirrors in

A cake of a dress – whipped to frou-frou

Scented dress of mustard seed, orange peel and almond milk

Glitter-bellied hummingbird dress

Ex-favourite dress, now not quite right

Perfectly acceptable dress, given the circumstances

*

Emotional State Seen Through A Pale-Haired Fringe

Dawn is coloured sweet pea and warbles with birds.

From bed, you notice how dust garlands

your fake yellow roses, but what now could

be gained by licking them clean? You could

plan menus, polish the mirrors, call your mother

and sweep the yard. Cleanliness, if not calm

in your reach. But, storm sultry, you lack

resources for comfort: the last velvet sleep;

legitimate wretchedness.

Others tell you, I too have felt alone.

Imagine them, teary on the sofa or wrenched

in the bathtub, all their wishes declined.

And then your own confines of lonesomeness,

where the at-boil kettle maddens the bully

of your memory, and no one there to see it blow.

*

We Should Be Very Sorry If There Was No Rain

For Sarah Crewe

I mention lately I’ve lacked a honeyed mood,

delicates have evaded me. Again I’ve spent too much

trying to ornamentally tile my life. The sofa’s worn

down where I always sit and though my diary’s

clogging up I don’t know how to project.

I am ashamed to want a someone. Social

engagements are propelled by wine,

as unease goes up, eyeliner goes on. Sometimes

I imagine you in your kitchen, stirring soup.

Sometimes I make broth and pretend it will work.

Darling, it seems there’s no awning

to shelter under. Or perhaps I’m under the awning

unable to step out. Someone might cake crumb

a path for me but it doesn’t do to rely on others

to ice your day. I can see the dead roses

are as pretty as the live, appliqué

sleep to my brittle concerns. I have an aspiration

you will recognise my handwriting, in time.

*

Igloo (Where the Wild Things Are)

When it is cold enough to slice the snow

we’ll build an igloo and we will live in it.

The igloo will be like a poached egg,

the snow dome hiding a hot yolk. We will grow

sharper teeth and bedtimes will be later.

I will be cook and you will make fire.

I have stolen sausages from mum

and this will do us for tea. There is a story

I can tell at night of a runaway child

and you will ask if it’s you. We have

two brothers, but they never let us take charge.

No one will know we are in the igloo,

but we’ll find a way of telling we’re safe.

Your best friend will be a bird and mine

will be a deer. The bird will bring us berries

and the deer will guard the door. Instead of talk,

we will have stronger thoughts. Our skin

will morph into something more warm. In summer,

we’ll make bricks of mud to dry in the sun.

*

High Voltage

Just as I woke, you stomped into my head

and I thought of everything that makes me admire you:

not just your sass and nerve (although

it does deserve an explicit mention ), but how

Neverland it is to spend time with you, like a pop-up theme park –

each day abundant with vivid wants,

like how you’re era-less, confident as a portrait,

inconsolably hungry, you talk easy as an adult –

seems even your glamour isn’t at the top of my list,

admiration being such an intimate reckoning of a

friend. If I can’t say it now, when?

Oh, there’s nothing ordinary about decadent warmth

real as foxgloves and glow sticks and winter birds,

did I tell you how much I want you to dance with me?

From Luxe (Salt Publishing, 2013).

Order Luxe here, here or here.

Visit Amy at Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat.

Read ‘Here, For Your Amusement’ and ‘”Too Gruesome!” at The Quietus.